Manatee effects on freshwater ecosystems

Ecosystem subsidies are energy and nutrients that are created in a donor habitat that are transported to a recipient habitat where they are used and have a substantial impact on the organisms living in the recipient ecosystem. For example, Pacific salmon migrating from the ocean to freshwater represents a subsidy because they are transporting marine nutrients to the freshwater ecosystem via their carcasses when they die and through their excretions. My PhD research is focusing on ecosystem subsidies.

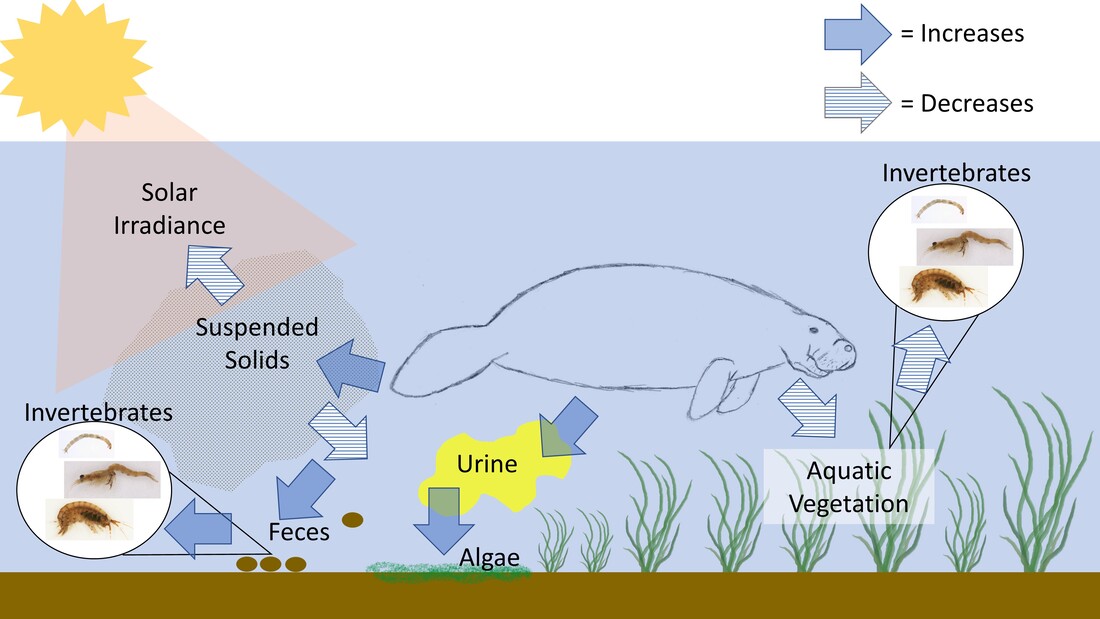

The Florida manatee primarily lives in marine ecosystems, but migrates into Florida’s warm, spring-fed ecosystems in the winter. The springs function as thermal refugia for manatees when the ocean temperatures drop below 20 degrees Celsius because unlike the oceans, springs maintain constant temperature of 22 degrees year-round. What are the ecosystem consequences of these 1,000 lb animals migrating into the springs in the hundreds? My dissertation research is trying to answer this question through a number a different studies by focusing on the potential role of manatees providing ecosystem subsidies through their feces and urine, both of which are rich in nitrogen. We are measuring if manatees provide nutrients to freshwater biofilms (algae, fungi, organic matter) and how manatee presence/absence affects biofilms. We are also studying how manatees affect nutrient uptake in the sediment and the water column through their excretion of urea and bioturbation (mixing) of the sediment. Urea introduced by manatees may may alter uptake of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate. Bioturbation of sediments may also alter nutrient uptake rates by releasing nutrients buried in the sand but also decrease light availability for biofilms. Finally, I am studying if manatee feces functions as a food resource for aquatic invertebrates and if manatee feces stimulates invertebrate production since manatee feces is undigested sea grasses and could be consumed by decomposers, similar to how leaf litter functions as a food resource for invertebrates. Manatees may subsidize the freshwater food webs through their feces by feeding on marine grasses and defecating in freshwater habitats.

The Florida manatee primarily lives in marine ecosystems, but migrates into Florida’s warm, spring-fed ecosystems in the winter. The springs function as thermal refugia for manatees when the ocean temperatures drop below 20 degrees Celsius because unlike the oceans, springs maintain constant temperature of 22 degrees year-round. What are the ecosystem consequences of these 1,000 lb animals migrating into the springs in the hundreds? My dissertation research is trying to answer this question through a number a different studies by focusing on the potential role of manatees providing ecosystem subsidies through their feces and urine, both of which are rich in nitrogen. We are measuring if manatees provide nutrients to freshwater biofilms (algae, fungi, organic matter) and how manatee presence/absence affects biofilms. We are also studying how manatees affect nutrient uptake in the sediment and the water column through their excretion of urea and bioturbation (mixing) of the sediment. Urea introduced by manatees may may alter uptake of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate. Bioturbation of sediments may also alter nutrient uptake rates by releasing nutrients buried in the sand but also decrease light availability for biofilms. Finally, I am studying if manatee feces functions as a food resource for aquatic invertebrates and if manatee feces stimulates invertebrate production since manatee feces is undigested sea grasses and could be consumed by decomposers, similar to how leaf litter functions as a food resource for invertebrates. Manatees may subsidize the freshwater food webs through their feces by feeding on marine grasses and defecating in freshwater habitats.

The effects of drought on aquatic insect emergence

Drought is becoming more common with climate change. The effects of drought on streams can be severe, resulting in increased water temperatures, loss of connectivity with the riparian zone, and in the most extreme cases, loss of longitudinal connectivity of the stream network. Loss of longitudinal connectivity can result in pool habitats being the last remaining refugia for aquatic life. We are measuring how an extreme drought in 2018, which resulted in the loss of longitudinal connectivity of the stream network leaving only isolated pools, affected aquatic insect emergence on the Konza Prairie Biological Station.

How leaf type affects the transfer of energy up the food web

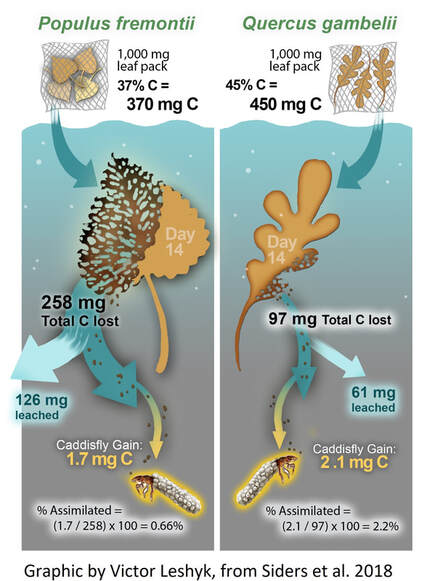

Leaf litter (dead leaves) can be the dominant source of energy in headwater streams because tree canopies can shade streams limiting algal photosynthesis. Leaves that decompose rapidly are often thought to be a higher quality resource for aquatic organisms than leaves that decompose slowly. Rapidly decomposing leaves often have high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus, which can be limiting nutrients for invertebrates, and low concentrations of lignin, tannins, and phenols, which decrease leaf decomposition rates. However, rapidly decomposing leaves disappear quickly, before invertebrates can use them as a food resources, whereas slowly decomposing leaves will persist in a stream for a longer period of time.

My master's research used leaves enriched with 13C and 15N stable isotopes to measure the transfer of carbon and nitrogen from leaves to invertebrates feeding on the leaves. We found that invertebrates feeding on slowly decomposing leaves incorporated more of the leaf mass lost during decomposition than invertebrates feeding on rapidly decomposing leaves. Our results demonstrate the importance of slowly decomposing litter as it will provide sustained energy and nutrients to food webs over a longer period of time than rapidly decomposing litter. Rapidly decomposing litter, however, can provide a quick pulse of energy to food webs and likely loses more mass to the microbial pathway than slowly decomposing litter.

My master's research used leaves enriched with 13C and 15N stable isotopes to measure the transfer of carbon and nitrogen from leaves to invertebrates feeding on the leaves. We found that invertebrates feeding on slowly decomposing leaves incorporated more of the leaf mass lost during decomposition than invertebrates feeding on rapidly decomposing leaves. Our results demonstrate the importance of slowly decomposing litter as it will provide sustained energy and nutrients to food webs over a longer period of time than rapidly decomposing litter. Rapidly decomposing litter, however, can provide a quick pulse of energy to food webs and likely loses more mass to the microbial pathway than slowly decomposing litter.